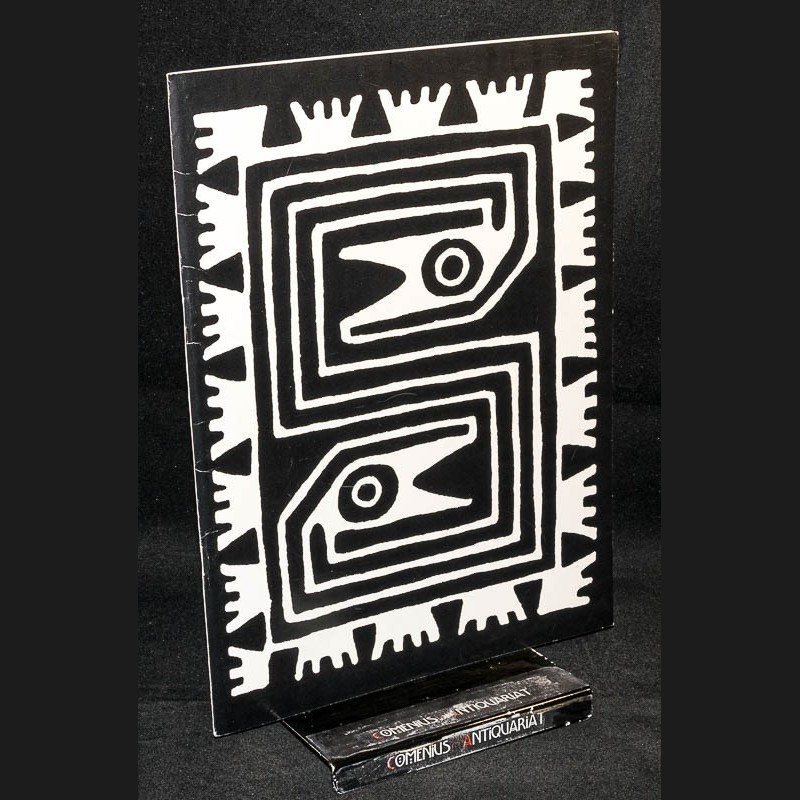

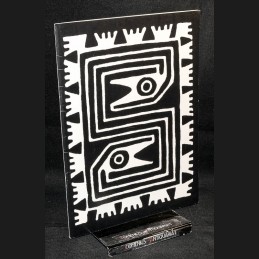

Bohlsen, Darrell,

Folk art of Mexico. Tampa: Tampa Bay Art Center, 1971. 32 Seiten mit Abbildungen. Kartoniert / geheftet. 4to. 111 g

* All works shown in this publication were retained from an exhibition of over 350 examples of Mexican Folk Art that the Tampa Bay Art Center organized and presented in the Fall of 1970. - Bibliotheksexemplar, diverse Registraturnummern und Stempel.

Bestell-Nr.157276

Bohlsen |

Ethnologie |

Voelkerkunde |

Kunstausstellung |

Ausstellungskatalog |

Lateinamerika |

Mexico |

Mexiko

INTRODUCTION

Last year an interesting incident occurred in an obscure Mexican village in Southern Mexico. There in the state of Oaxaca the little village of Miahuatl6n was hosting some of the world's foremost scientific teams which were assembled to observe and record the fleeting seconds of a total eclipse of the sun. Some hours, before the climatic moment, one of the scientists was being interviewed and was in the process of explaining some of the marvelous feats their scientific gear could accomplish. But when it came time to make reference to the lens cap of the powerful telescope that protected the delicate lens up to the seconds before the event, the scientist pointed out that the cap was to be removed by hand. This was unlike most of the other parts of the operation which were being run through an automatic computerized control system. When the interviewer asked why this exception, the scientist quickly explained that his team had gone through too much trouble and expense coming all the way to Mexico, to study and record the eclipse, to allow a mechanical failure in this simple but crucial step to ruin the entire project. Instead, for basic insurance, he or one of his team members would step up and remove the cap by hand when the time came.

In an age filled with dadaistic experiments and pessimistic philosophies this Miahuatlen incident becomes one of those curious examples that spring up now and then to reaffirm man's confidence in the things he does with his hands. Another would be an example of authentic Mexican Folk Art. Certainly, part of the fascination of these well made Mexican folk objects is the revealed supreme inner confidence of the artisan and his attitude of near infallability toward what his hands can do.

Rudolf Arnheim once wrote quite simply that, "Art is the most concrete thing in the world." Applying this to our folk art items, Arnheim is merely asking us to remove all the "dehydrated aesthetic concepts"2 about them and take them for what they are: statements of "carino", tender, loving care, and concern for the common, everyday items the artisan finds avail-able to him. And this kind of attitude toward the immediate things in the environment certainly is most welcome in our age of ecological dis-asters. The late George C. Vaillant observed that "the ordinary modern floats like Mohammed's coffin, without contact with the earth on which he lives or the universe of which he is an infinitesimal part."3 Perhaps, then, our Mexican artisan can help us return to the tree of natural existence from which Vaillant sees us separating ourselves with the saw of our Western reason.4

Well, Vaillant's allegorical tree certainly seemed attractive to at least this Western anglo observer as it was seen growing in the humble workshop-home of artisan Candelario Medi-6n, who lives in a small village just out-side of Guadalajara, Jalisco, and whose situation is such that it serves as a typical example for the following general observations of the world of Mexican folk art.

First, there is the fact that in his village, Candelario Medr6n is neither estranged nor exalted because of his work. The fact that he, and what he makes, is totally accepted into the village life means that he occupies a position neither lower nor higher than his neighbor, the baker. This rather nonchalant attitude of the villagers toward their local maker of beautiful things may strike the outsider at first as ignorance and a lack of sensitivity toward local talent, but he must remember that he is observing a society in which beauty is a fact of life and not something to be seen just on a Sunday afternoon at the gallery.

In writing about the popular art of the state of Michoac6n, Dr. Daniel Rubin de la Borbolla steers us toward another important observation: The family workshop, which assigns roles in the operation to the children as well as the adults, is the basic unit of production of art-craft work.5

To see how smooth and rewarding this arrangement can be, I recommend visiting the workers of reed (see plate V) who dwell in the villages sur-rounding Lake P6tzcuaro. In fact in this same area of Michoac6n there are to be found many examples where not only families but entire villages are united in the production of just one item. A good example of this is the village of Santa Clara de Cobre (Villa Escalante) which produces prac-tically all of the copper craft work found in Mexico. (see plate VII)

In the case of Candelario Medran, it was actually his teenage son who was putting the final touches on the work shown in plate I when I arrived to take it. The sociological and aesthetic implications of family and community craft groups certainly need to be explored further for their possible con-tributions to our modern life style.

There is, however, an element entering the world of Senor Medr6n which may change all of this. Something that is really not new. Frances Toors observed it as far back as 1939.6 And that is the increasing role and power of the foreign (mostly North American) purchaser of Mexican folk art. The

changing of the product to suit this new buyer's tastes and pleasure, the emphasis on volume, and the disruption of the direct personal exchange between consumer and maker are only some of the factors that are affect-ing adversely the traditional quality of Mexican Folk Art. The single most important item, however, threatened by this introduction of modern means of production is the long nourishing traditions that form the creative well from which Candelario Medran, and men like him, draw. It is really very difficult for us, from an orphan society, to fully appreciate the strengths and supports that come from roots of human experience going back dozens of generations. Indeed for us it demands an act of poetry to grasp the significance of having a living connection stretched over two continents with men such as Topiltzin QuetzalcOatl, the god-man patron saint of the Indian artisan; Nezahualcayotl, the great Nahuatl poet-king; Erasmus, the great European humanist and intellectual hero for the sixteenth century Spanish missionary; Don Vasco de Quiroga, the sixteenth century missionary bishop who with great single-mindedness promoted the arts and culture of the indigenous population. All of these men are still living in the hands and the works of the Mexican folk artist.

But they are slowly dying. The reader should note, however, that the pessimism is mine. It is I, the outsider, who can see the hundreds of ways the Mexican creative forces are being destroyed. The insider, Candelario Medran, seems quite calm and at ease amidst all the changes. Does he do this out of ignorance? I would say no. Rather, let me suggest that the name of the game is Faith. Written on the face of Candelario, as well as imprinted on the things he makes, is the ancient Nahuatl message for mod-ern man: after four abortive attempts we are living under the fifth sun. It is the new sun for a new age. An age of movement, harmony, and creativity. It is the age of the god—QuetzalaSatl, our creator and our source for culture, art, and all that is good within us. And it is only he who can, and will, finally defeat the gods of war and destruction.

Darrell Bohlsen February 19, 1971 MA

1 — Rudolf Arnheim, Art and Visual Perception (London: Faber and Faber, 1954), p. x.

2 - Ibid.

3 - George C. Vaillant, The Aztecs of Mexico, Penguin Books (London: Doubleday, 1960), p. 142.

4 - Ibid.

5 — Daniel F. Rubin de la Borbolla, Arte Popular de Michoacan ("Popular Art of Michoacan") (Morelia: Museo Michoacano I.N.A.H., 1969), p. 2.

6 - Frances Toors, Mexican Popular Arts (Mexico: Frances Toors Studios, 1939) p. 4.

frais de transport

frais de transport

Google Mail

Google Mail